Website Single Sign-on (SSO): great idea or privacy nightmare?

We’ve all been to a new website that offers us the option to ‘log in with Facebook or Google’. Very handy. Or is it?

What’s really going on here and what exactly are you sharing?

This option to log in via social media is called SSO (Single Sign-on). There are are a couple of different technical methods for how it is deployed – we won’t be going into the technical differences in this article, but rather we will address whether it’s safe in terms of both online security and, more topically, the protection of your data privacy.

Some basics before we get started;

- SSO is used on many major sites and is becoming more popular because it’s seen as a way to increase the number of people on new platforms by minimising the sign-up process.

- Facebook and Google are the most common and popular as they are the services that most people have.

- SSO reduces the number of passwords to remember.

- It gives the impression of greater security, backed by the bigger, recognisable sites.

- It speeds up login.

What is SSO?

There are two basic types of SSO that work using the same principle of you using one website or application’s logins to access another – also known as cross-domain sign on. We’ll be discussing the type known as ‘federated’ SSO. It means that you provide permission for one website to set up and log into another website (where you have a registered account). We’ll be coming back to permissions later.

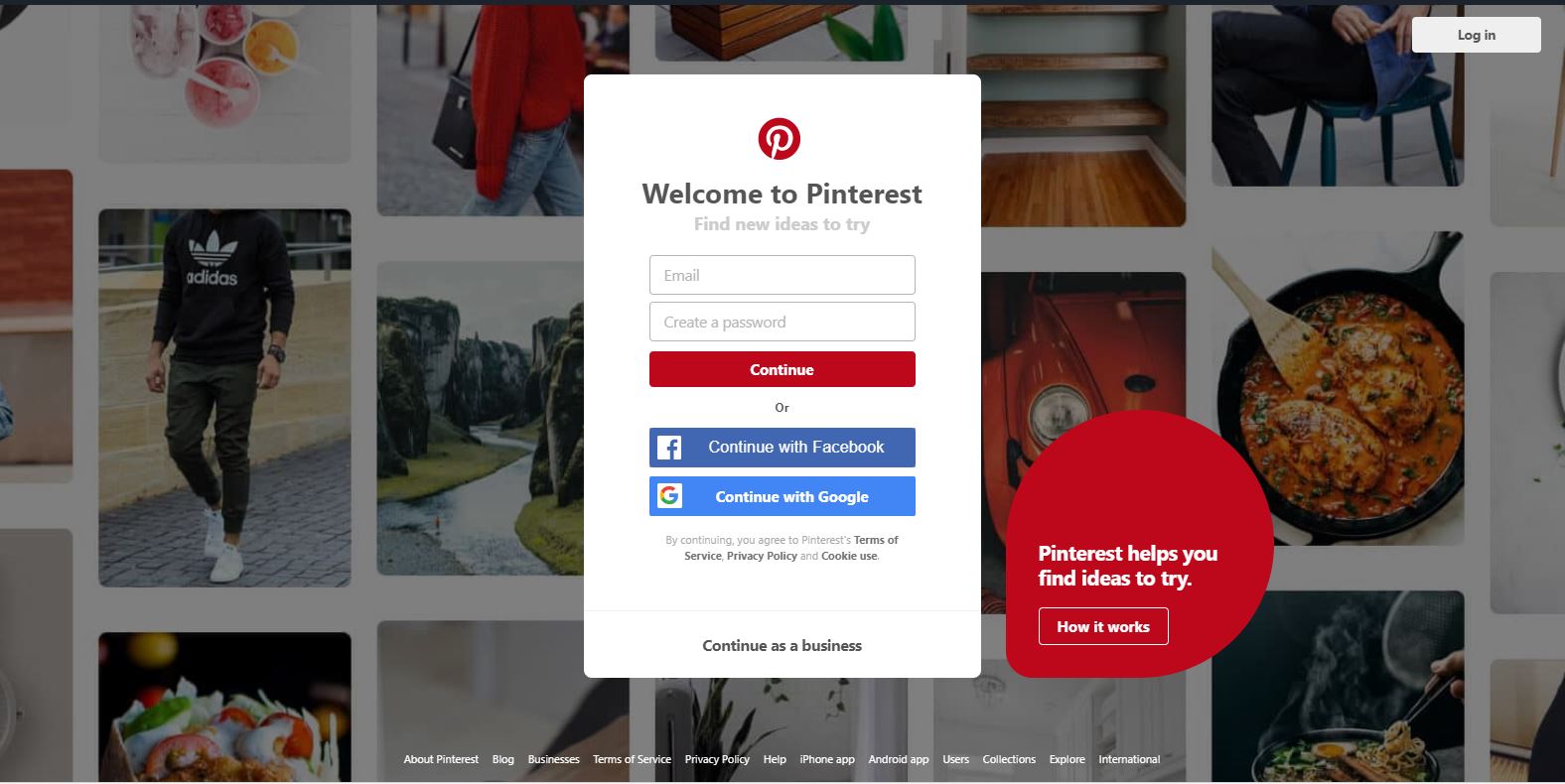

Let’s say you have a Facebook account. Facebook store your username and password on their servers. It’s encrypted. Google does the same, as do many others. If you then go to another social media platform or website that offers SSO (Pinterest, for example) you can sign up and log in using the credentials from your Facebook or Google account.

A sharing of credentials, along with the rules as to what the ‘child’ website can now access from the ‘parent’ site (and vice versa), are handled through the few clicks you go through when agreeing to the seemingly innocuous T&Cs. You’re granting access to one website with agreed credentials (we’ll call them ‘logins’ from now on) through authorised sessions to access another site.

There are now two websites that have the logins. One (or both) website(s) can now access details from each other, depending on what the permissions were when you agreed to them. It makes for a seamless and more connected network.

SSO and security

Some say that SSO is a bad idea because you’re putting all your eggs in one security basket and if one site gets hacked they all do. This is not true. The logins (username and password) for the site that you use as the originator or ‘parent’ (in most cases Facebook or Google) will be stored in an encrypted format. That means the logins cannot be deciphered and then used on other sites.

In fact, SSO improves security – and let me explain why. One of the most common security vulnerabilities are the fake emails – called phishing emails – that appear to come from an official site (such as Facebook), saying that there was suspicious activity on your account and asking you to log in and reset the password. The link takes you to a site that looks like the real one. But it isn’t. When you reset the password, what you actually do is give the password to the hackers. However, SSO uses authorised sessions between the two connected sites and are based on the logins from the parent to the child site being correct within the same session. If your logins change on the parent site the access to all connected child sites is temporarily rescinded until access is granted again with a successful login and reconnection via the parent site.

So – set one, decent password once for your parent site and set up 2FA (two-factor authentication) on it too so that you get an SMS or use a code generator such as Google Authenticator (Facebook has its own). That way, the only way someone can get into your sites to not only have access to your password but also your phone.

From a business perspective, SSO also makes financial sense. A huge part of an organisation’s IT support comes in the form of a request for resetting of passwords. Using SSO would significantly reduce the number of these if the organisation used a company set of SSO credentials.

Useful tip: If you have ever wondered whether your logins have been compromised from a previous website hack you can visit this very handy website – www.haveibeenpwned.com – simply enter your email address in and it’ll tell you if your email address and logins have enter been compromised and most likely the site from which they were stolen. One of the most common in the UK was the major hack of Linkedin some years back – millions of logins were stolen.

SSO improves user experience.

How many times have we gone to log in to something and not been able to because the password was reset after the last time because we forgot it and that site now requires you to come up with something new, or your previous password now doesn’t meet the minimum requirement in terms of number of letters, numbers and special characters. We’ve all been there.

SSO means that you set a good, strong password once and then deploy it on all subsequent sites. It’ll give you quicker login, reduced frustration and it’s all a bit more fluid and connected.

The downside is that if you ever need to change the parent website (your Facebook or Google account for instance) you will then need to update that password on all other sites with a SSO. But a regular review of what sites are connected is no bad thing anyway.

This is following good cyber security principles.

But…

What about privacy – what exactly am I sharing?

You’re not sharing the logins themselves in a readable format – they’re encrypted and connected to the ‘session authentication’. This means that the parent website is granting access to the ‘child’ website using a temporary approval to do so.

However, you’ll recall earlier I mentioned about permissions? Well, when you set the SSO up at the beginning, you will have had to accept T&Cs – like all things on the internet. Pages and pages to flick through to eventually get to the ‘accept’ button. You’re worn down by then – just log me in!!

In that permissions stage you are granting the child website access to all the content from the parent site that it asked for. Yes, suddenly all the stuff that was on your Google or Facebook account has now been shared with this other site that asked permission to see it all and you just said ‘yes’.

Oh.

Most major sites don’t ask for anything beyond what they need – name, email address, logins (all encrypted). However, in light of recent events with Facebook and Cambridge Analytica how can we be sure that we aren’t granting access to our entire life and data profile because we don’t want to read 94 pages of T&Cs?

You have rights in terms of what data people can capture and hold about you and how they use it.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ll have heard about GDPR – the General Data Protection Regulation.

How does this affect GDPR obligations?

Let’s be clear – GDPR is a good thing. An admin and logistical monster but good in principle. Hopefully when the dust settles people will be all a bit more data privacy aware and respectful of how other people’s data is used. But what about technology that’s out there and has spread data to the four winds?

So, this leads me to the question:

“How can GDPR and privacy rules been maintained when one site is passing information directly to another and another… without all parties in the chain getting permission from the subject?”

“How can the user control what data is shared with another site and all other sites thereafter?”

If the GDPR process is strictly adhered to, when a user requests an SAR (Subject Access Request) to one site (the ‘show me all the data you have on me’ process), all other sites to which that login is connected and the data has been shared must perform the same. Such as in the case of sites that run federated SSO.

What? So, if one site has shared the data with another and they in turn have shared it on (whether with or without your permission) just because I wanted to log in quicker and faster what’s the point of GDPR? And how will I ever truly control my data privacy?

Yes, exactly.

Example.

Some years ago, we were commissioned to build a business-based social network. Part of the specification was to add SSO so that it would aid in the speed of signups and users. At that point we had not deployed a site with this feature as it was fairly new.

Once we had researched how the code worked what struck us was that, assuming the user signing up agreed to the terms, we could scrape any of the data we liked from the site that was used to sign in. Some would say that this is down to the user and their own due diligence of reading the endless stream of T&Cs that most spin through to get to the ‘accept’ button.

However, because we hadn’t configured the site with any limitations and through our own inexperience, we were able to scrape the entire profile data, images, files, links – everything the user had collected from the Facebook account they used for signing up to this new service.

We sat in silence for about 10 minutes looking at each other in horror and then quickly deleted everything. We revisited the specification and limited it to just profile name, email address and the encrypted password (which is never visible).

Shocking.

So, what’s my point?

My point is this. We want to live in a connected world with everything at our finger flicks and gestures. Logins, schmoggins – who needs those. Hello SSO.

But then, when big data ‘breaches’ occur (both technical ones or misuse) we’re all up in arms –

“it shouldn’t be allowed – someone should do something.’

But you agreed to it in the T&Cs you flicked through. So, who’s really at fault?

The fault is us. We want all the good stuff but without the bad stuff and we want it for free. Well, nothing is free – the price?

Your data privacy.

So, should I use SSO or not?

SSO is an excellent thing – there’s no denying it. It’s superb for overall cyber security from most perspectives. Passwords, unauthorised access prevention, phishing vulnerabilities – all that.

However, it won’t protect users against human behaviour of just being lazy and agreeing to T&Cs that expose their data privacy.

GDPR will help route out those that abuse data privacy eventually but won’t prevent people from themselves and willingly or otherwise sharing their most valuable asset. Their data privacy.